Mark Pyman and Paul Heywood’s Sector-Based Action Against Corruption: A Guide for Organizations and Professionals is not for everyone. If your goal is to improve a nation’s CPI score, attack grand corruption, or realize some other broadly stated, national level objective, stop here.

But if, as the authors explain, you “need to acquire competence in recognizing, analyzing and dealing with corruption” in a particular organization or process, and if you believe that “corruption Is as much a management issue as it is a political one,” download it immediately. (And thank whoever made this must-have book open-source.)

Pyman’s and Heywood’s careers both combine hands-on work helping government agencies and corporations curb corruption with serious engagement with the learning on corruption. And it shows. From the rigor they insist be brought to bear to specify identifiable, tractable corruption problems (corruption due to a non-meritocratic civil service is not one; conflict of interest in hiring is) to the disciplined approach they present for selecting the best measures for remedying them.

They break the process for “recognizing, analyzing, and dealing with corruption” into four steps labeled SFRA:

S: Tackle corruption at the sector level. By sector, the authors mean either an organization, a government agency like a health ministry or police department or a process, managing public funds or procuring goods and services. The advantages of a sector-based approach are many. There are individuals in every sector dedicated to its mission, doctors committed to patients’ well-being, engineers to the delivery of cheap, reliable power, procurement to securing best value for taxpayers. They can be enlisted to help understand why and how corruption has taken root and point to places where it has been successfully weeded out. They provide the foundation on which reform will sit.

F: Focus on specific issues. The key to combating corruption, the authors argue, is concentrating efforts on “specific, comprehensible issues,” ones that sector personnel “can collectively recognize and address.” Otherwise, as the authors say and this writer has observed again and again, “the momentum necessary for addressing the problems [are] never developed or sustained.”

The identification of “specific, comprehensible” issues in a sector requires the help of those who work in it. They bring the granular knowledge of people and processes needed to spot corruption vulnerabilities, but getting them to open up about the where, the why, and the who behind corruption is often challenging. To prompt discussion, chapter four lists the types of corruption typically found in policing, defense, education, and health. It also provides a more general list that can help kick start a conversation about corruption vulnerabilities in any sector.

R: Generate a list of plausible measures for remediating the corruption. Much of the book’s meat is in the chapters on remediation. The authors present it as a two-step process. The first, described in chapter six, involves what they term a “stand-back moment,” a look at “the broader picture.” They offer a structured decision-making process for answering the broad, unavoidable question that haunts all reform efforts: “how the local political circumstances can be navigated so as to have the best chance of delivering the desired change.” That might engaging the broader political community in the proposed changes, or alternatively advancing reforms quietly.

It’s a judgment call, and like many others that must be made in deciding how to frame possible changes, there are no sure answers. What the authors prescribe is a process for producing well-informed judgements.

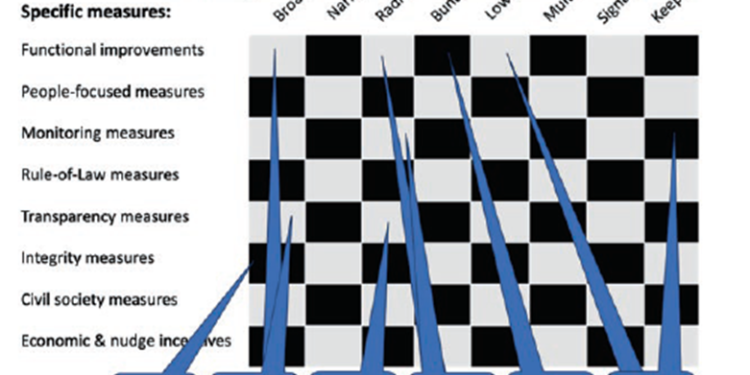

The second step in identifying possible remedial measures is the listing specific one most likely to eliminate, or at least curb, corruption in the sector. That step is the subject of chapter seven, the book’s longest; for by now many different reforms have been tried. Chapter seven contains, by the authors’ count, eight categories of detailed remediation measures with 64 sub-categories and 65 examples. The exhaustive list is meant both to ensure reformers don’t overlook anything that tried elsewhere and to reassure the hesitant that there are places where reform has produced results.

A: Choose the measures to act upon given the political, economic, and social context. In chapter eight the authors explain how to combine the results of chapter six, options for how to broadly frame reform, with those from chapter seven, feasible, specific reforms, to arrive at “the best action to take in the circumstances.”

The process again involves a structure making choices, this one in the form of a matrix with the broad categories as columns and the detailed measures as rows. The different combinations are then examined through ten “lenses,” the authors term for different ways of thinking through how the reforms will play out in practice: who will support them and who will oppose them; how the election calendar will affect the choices; what resources are at-hand, and other intensely practical matters likely to make a difference between success and not. An example matrix, shown on page 131, is reproduced below.

A laudatory review must include a few nits to be credible. My three.

- Recent research (hereand here) suggests the authors are overselling the value of “nudges,” subtle ways of influencing behavior by, for example, requiring public servants to periodically sign a document pledging to observe ethics rules.

- When convening a group of personnel to candidly discuss corruption vulnerabilities, younger, less experienced personnel may remain quiet, deferring to older, higher-ranking individuals in management. Understandable, but often it’s younger staff, closer to day-to-day operations, who have the most insights on corrupt practices. (UNODC’s State of Integrity, a nice complement to Pyman and Heywood, provides several solutions to what it terms “senior bias.”)

- Finally, an especially costly form of corruption, bid rigging in road construction and other infrastructure contracts (here), drew nary a mention.

But these, and other minor nits I am sure others can find in a book of such breadth and depth, in no way detracts from what Pyman and Heywood have produced. An invaluable guide to making real, measurable progress combating corruption.