By Jarrah Kawusu-Konte

On a scorching afternoon, Aminata Fawundu clutches her four-year-old son to her chest as she waits outside a mud-walled community health post. The child has been running a fever for days. Inside, the nurse apologizes again. “No paracetamol. No antimalarial. Come back next week.”

But Aminata has already walked several miles. Next week may be too late. This is not an isolated story. It is a national metaphor, a people condemned to suffer in silence while their health system gasps for life.

A Legacy of Hope Betrayed

In 2010, the world watched with cautious optimism as Sierra Leone launched its Free Health Care Initiative (FHCI), a groundbreaking initiative introduced under the leadership of former President Ernest Bai Koroma. The initiative targeted pregnant women, lactating mothers, and children under five, a demographic most vulnerable to preventable diseases and early death.

Internationally applauded for its boldness and vision, the initiative was supported by the United Kingdom (UK)’s Department for International Development (DFID) (now FCDO), United Nations Children’s Fund

(UNICEF), the World Health Organisation (WHO), and the Global Fund. Its goal was simple yet revolutionary in Sierra Leone’s context: to eliminate consultation fees and basic drug costs, which had long been a crushing barrier to primary health care.

The initiative rapidly showed results. According to WHO and UNICEF Joint Evaluation Reports (2011–2016):

Institutional deliveries increased by over 45%. Maternal mortality dropped from 1,165 per 100,000 live births in 2005 to 796 by 2015. Child mortality declined from 160 to 114 deaths per 1,000 live births. A 400% increase in health facility visits was recorded within the first two years.

A Dream Deferred

Fast forward to post-April 2018, and the story has changed drastically. Despite the Bio administration’s rhetorical commitment to “human capital development,” the FHCI has seen systemic neglect and administrative decay. According to the 2022 Ministry of Health Service Delivery Review, key FHCI indicators have stalled or reversed:

Stockouts of essential drugs for children and pregnant women occur in over 60% of public facilities, per Médecins Sans Frontières (2023) report; and out-of-pocket spending on health has increased to 48%, compared to 36% in 2016 (World Bank Health Financing Report, 2022). What was once a symbol of national resolve has become a case study in missed opportunities.

“In the early years of the Free Health Care Initiative,” Jeneba Nyallay, a Freetown resident of Dwarzak recalls, “you could walk into a clinic and be seen with respect and receive medicine. Today, women die with prescriptions in their hands and tears in their eyes.”

A community health officer in Bo, requesting anonymity, put it even more bluntly: “The initiative still exists on paper. But in real life? It’s gone. We now ask mothers to ‘find a way’ for even gloves and syringes.”

The Human Toll

The cost of this regression is measured both in data and in the buried dreams of children and mothers. In 2023 alone, over 80,000 children under five were admitted for malaria in clinics that had no antimalarial drugs in stock, according to credible international reports. More than 10,000 childbirths occurred without skilled attendants in government facilities due to midwife shortages and strikes. Stillbirth rates rose to 27 per 1,000 births, among the highest globally.

Development economists point to the Andersen Health Behavior Model, which emphasizes that access to care depends not just on need but on “enabling factors” like affordability, physical access and provider availability, all of which have deteriorated in recent years.

The Political Will to Heal

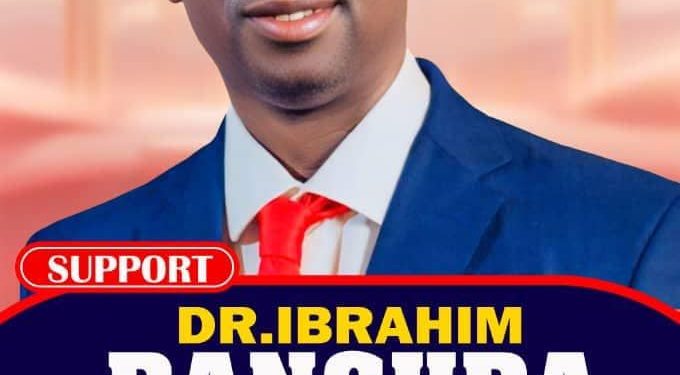

Dr. Bangura insists that reversing this decay will require courageous leadership, community-based solutions, and restoration of the original FHCI architecture, supported by a culture of accountability.

“We do not need to reinvent the wheel,” he said. “We need to remove the politics from people’s pain. The Free Health Care Initiative gave hope. Let us not bury it.”

What should be done?

• Performance-based pay for frontline health workers

•Digital tracking of drug inventories to prevent stockouts and theft

•Reinstating the FHCI Taskforce with civil society oversight

•Restoring district-level health planning autonomy to improve responsiveness

Drawing inspiration from the Grossman Health Capital Theory, we should treat health as both a consumption and investment good. “When you fix health, you fix productivity, peace, and pride,” said Dr Ibrahim Bangura.

Conclusion: A Broken Promise, A Chance for Redemption

The late Kofi Annan once observed that “There is no tool for development more effective than the empowerment of women.” In Sierra Leone, “that empowerment begins with surviving childbirth, having a healthy child, and walking into a clinic without fear or shame, ” Bangura asserted.

The Free Health Care Initiative was not perfect, but it was a promise kept to protect life, even when money was short. Today, that promise lies in tatters. The time has come for a new leadership to revive the vision, to restore the trust that once made Sierra Leone a model in the region.

As Bangura once noted during one of my conversations with him, “A government that cannot guarantee medicine for children has no business asking for a third term in power.”

But this important task of healing the nation, restoring hope, and building a people–centered health care system that is well resourced and well managed starts with the APC delegates. Elect Dr Ibrahim Bangura for better healthcare in Sierra Leone.