By Alvin Lansana Kargbo

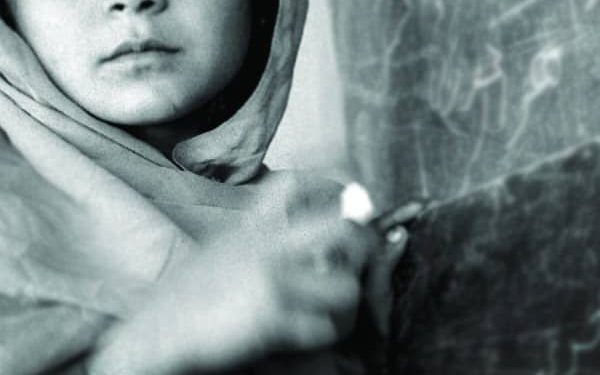

Mariama Kamara, a bright and determined 17-year-old, recently sat the Basic Education Certificate Examination (BECE) at Government Rokel Secondary School in the central part of Freetown. She began her academic journey at Wallace Johnson Primary School, where she took the National Primary School Examination (NPSE) and excelled, earning a place at one of the capital’s oldest government secondary schools.

But despite completing nine years of basic education in post-war Sierra Leone, Mariama knows almost nothing about the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) or the recommendations it makes to heal the country after the devastating civil war that lasted from 1991 to 2002.

“I’ve heard about the war from my parents, mostly at night when they talk about things they went through,” Mariama says quietly. “But in school, we don’t learn about what happened in detail. No one has ever taught us about the TRC or how Sierra Leone tried to fix what went wrong.”

Her statement highlights a worrying truth; more than two decades after the war, the next generation is growing up unaware of the official efforts to rebuild justice and national unity.

The TRC, established in 2002 as part of Sierra Leone’s transitional justice process, was tasked with uncovering the truth behind wartime atrocities, promoting reconciliation, and preventing future conflict. In its final report published in 2004, the TRC called for a comprehensive peace education program to be taught in all schools, ensuring that children understood the roots of the war, its consequences, and the country’s collective journey toward healing.

However, that vision has yet to materialize in any meaningful way.

At Government Rokel Secondary School, where Mariama completed her BECE, Augustine Kallon, a social studies teacher with over 12 years of experience, admits that the TRC is largely absent from the national curriculum.

“To be honest, we don’t teach the TRC in any structured form,” Kallon says. “We cover a chapter or two on Sierra Leone’s history, and we mention the civil war, but the focus is very general—dates, causes, and consequences. There’s little to no space for discussion about what the TRC did or what it recommended.”

Kallon explains that even though he personally understands the importance of teaching post-war justice, there are no textbooks, no training, and no guidelines provided by the Ministry of Education.

“Students ask about the war sometimes, but because we’re under pressure to complete the syllabus and prepare them for exams, we don’t have time to go deeper,” he says. “Peace education is treated as optional, when it should be essential.”

For students like Mariama, the lack of structured education on transitional justice means that vital lessons about accountability, healing, and civic responsibility are missed. They grow up without understanding the depth of trauma their country experienced, and without the tools to prevent similar divisions in the future.

“I don’t know what ‘reparations’ mean,” Mariama admits. “I don’t know if victims got help. All I know is people died and suffered, and now we try to move on.”

This lack of awareness doesn’t just impact students academically, it also shapes how they engage with society.

Isatu Sesay, Executive Director of the Sierra Leone Human Rights Network (SLHRN), believes this knowledge gap is a national failure that must be urgently addressed.

“When young people are not taught about the TRC and what it stood for, we lose the opportunity to pass down critical lessons about justice, forgiveness, and reform,” she says. “We can’t expect the next generation to protect peace if they don’t understand the fragility of it.”

She believes that the Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary Education (MBSSE) must take the lead by integrating peace education and transitional justice into core subjects, and by providing training for teachers.

“The TRC made specific recommendations for education reform. We can’t keep treating those recommendations as suggestions, they are essential for preventing future violence and division.”

A 2022 review by the Human Rights Commission of Sierra Leone found that less than 25% of secondary schools in the country have any active peace education initiative, and none have a curriculum fully aligned with the TRC’s educational goals. Meanwhile, a whole generation of students, including those born after the war, are growing up with little knowledge of their country’s efforts at justice and reconciliation.

When contacted for comment, a senior staff from the Ministry of Basic and Senior Secondary Education (MBSSE), Sheku Ngakui, acknowledged the importance of integrating transitional justice education but said there are “competing priorities” within the education sector and a lack of resources.

“The Ministry recognizes the recommendations of the TRC and supports the idea of peace education,” he said. “However, the development of a nationwide peace curriculum requires technical input, funding, and broader curriculum reform, which is ongoing but slow.”

Education rights advocates argue that this response reflects a troubling lack of urgency.

“Twenty years is not a short time,” says Isatu Sesay of the Sierra Leone Human Rights Network. “The Ministry cannot keep hiding behind bureaucratic delays. Teaching the TRC’s work is not a luxury, it’s a responsibility.”

Among the Truth and Reconciliation Commission’s recommendations relating to education were:

• Develop and introduce a comprehensive national peace education curriculum.

• Train teachers to handle sensitive topics about the war and its impact.

• Support student-led peace clubs in schools.

• Use education to combat stigma faced by victims, especially women and children born of rape.

• Ensure that young people understand civic responsibility, accountability, and non-violence.

Yet two decades later, few of these goals have been realized.

As Sierra Leone continues to build its post-war identity, education must serve as a bridge between past pain and future progress. For Mariama and thousands like her, understanding the truth of the TRC is not about dwelling on the past, it’s about shaping a future where justice is understood, and peace is protected.

“I want to become a teacher one day,” Mariama says with a smile. “Maybe I’ll be the one to teach the TRC to students, if someone teaches it to me first.”

Until the government invests in peace education and takes its own reconciliation roadmap seriously, the silence in classrooms will echo the silence that once followed the guns.

This story is brought to you with support from the Africa Transitional Justice Legacy Fund (ATJLF) through the Media Reform Coordinating Group (MRCG), under the project: ‘Engaging Media and Communities to Change the Narrative on Transitional Justice Issues in Sierra Leone.’