By Ahmed Sahid Nasralla (De Monk)

Once upon a time, there was a nation (and still is) where gold and diamonds lay side by side with bauxite, iron ore, rutile, and oil.

A rich ocean embraced her shores, with green mountains stacking majestically atop one another.

The seasons came with rain and with sun. Vast acres of fertile land flourished with cocoa, coffee, piassava, rice, and palm kernels for palm oil. Plants, fruits, and vegetables blossomed joyfully.

An endless stretch of clean sandy beach separated the coast from the ocean.

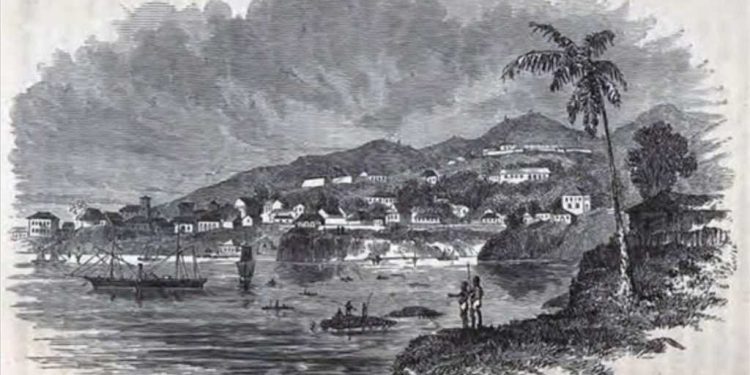

Then came the voyage of a Portuguese sailor named Pedro da Cintra. White history says he discovered this small nation. Black history did not argue. It was during the rainy season, and the roaring thunder convinced the sailor that his ship was sailing through a jungle of lions. The massive mountains seemed to him like resting lions. Thus, he named her ‘Sierra Lyoa’, meaning Lion Mountain.

News of the discovery spread. European voyagers, mainly British, began stopping along the coast to fetch fresh water and trade with the early settlers.

These settlers, sadly, fought among themselves and took prisoners of war. In their trade with the White men, they sold these prisoners, their own brothers and sisters. as slaves. They also exchanged fruits, ivory, carvings, gold, and camwood for rum, guns, gunpowder, tobacco, clothes, and beads.

The White men chained the slaves, packed them onto ships, and took them across the seas, to Britain as servants, and to America to work the vast plantations.

Yet among the British, a few good men, like Granville Sharp, Thomas Clarkson, and Lord Mansfield, fought to return some of these poor Black souls to Lion Mountain.

Thus, Lion Mountain was reborn as Freetown, a settlement for freed slaves. They built houses, constructed roads, and started trading among themselves. But soon war broke out between the new settlers and the old, burning their communities to the ground.

Again, the few good White men sent help: building materials, food, clothing, and money, to rebuild.

The British government, seeing more than friendly people and beautiful mountains, sent administrators to take over governance. They brought Christianity, built schools, and taught a favourite school song: ‘Learning is better than silver and gold.’ The British never mentioned the people’s diamonds, but the people chose to learn, and the British chose to teach (and mine).

The British taught and mined. The people learned and learned, until they were satisfied they had learned enough to rule themselves. They asked the British to leave.

“Oh sure, we’re leaving. But you guys take care of yourselves, okay,” the British said, and left.

The people then chose a gentleman named Sir Milton Margai, for his exceptional role in securing their freedom. His leadership (1961-64) laid the foundation for development, unity, political tolerance, and a free and responsible press.

Milton was succeeded by his brother, Albert Margai. But unlike Milton, Albert laid the foundation for collapse: tribalism, corruption, political intolerance, election rigging, and caged press freedom.

Albert was followed by Siaka Probyn Stevens, whose rule was as dark as his complexion. He developed a crude way of leading. When the people asked for money, he pointed them to the farms, saying money grew there. When they said they were managing (local slang for struggling), he joked that he didn’t know he had so many managers in the country. When they teased him about his big nose, he laughed and compared it to the long queues for rice.

Stevens understood the psychology of his people, and used it to contain them. He normalised corruption so long as it didn’t threaten his dictatorship. Those who challenged him were charged with treason and hanged.

When Stevens felt his end was near, he handpicked Joseph Saidu Momoh, a pot-bellied army officer who seemed a dumb character straight out of George Orwell’s Animal Farm, to succeed him, securing his own protection.

Momoh inherited a nation ready to bleed. And bleed it did.

The people rebelled; the army reacted.

One morning, soldiers stormed Freetown in tanks and armored cars, supposedly to inquire about their supplies. Momoh read the signs, fled the scene, and the soldiers seized power under the National Provisional Ruling Council (NPRC), ending 25 years of despondency.

The NPRC were welcomed with overwhelming civil affection. But they soon lost their way, executing 18 Sierra Leoneans on trumped-up coup charges. Their young leader, Captain Valentine Strasser, was ousted by Captain Julius Maada Bio, who, under civilian pressure, quickly organized elections.

In the middle of the war, Alhaji Ahmad Tejan Kabbah was elected president.

Kabbah was tolerant, some say too tolerant. He trusted even his enemies and seemed unaware of the country he was meant to lead. Before he found his bearings, he was overthrown by disgruntled soldiers calling themselves ‘Honourables’ under the Armed Forces Revolutionary Council (AFRC).

Led by Johnny Paul Koroma, a former prisoner who claimed divine appointment, the AFRC was rejected by both the people and the world. To strengthen his grip, Johnny Paul invited the rebels, forming the so-called People’s Army, and led the nation straight to hell.

From exile in Guinea, Kabbah fought back with ECOMOG’s help and reclaimed power. The Honourables fled into the jungle. Citizens, fuelled by rage, hunted down alleged junta collaborators, burning and killing with merciless ferocity. Kabbah’s government tried, executed, and jailed many.

When the Honourables regrouped for a comeback, darkness engulfed the land once more. Citizens burned their homes, public buildings, killed each other, and drank blood.

ECOMOG and the United Nations returned to save the people once again. A government of national unity was formed. Johnny Paul became Chairman of the Committee for the Consolidation of Peace. Rebel leader Foday Saybanah Sankoh was made head of the country’s mineral resources, effectively a vice president.

But Sankoh’s rebels captured 300 UN peacekeepers. Enough was enough. Citizens stormed Sankoh’s residence at Spur Road. Sankoh fled but was captured by the people of ‘Dorti Road’, and later died while on trial for crimes against humanity.

Then, a new dawn emerged.

White men came with a Special Court to try the warlords, and a Truth and Reconciliation Commission to heal the wounds.

Kabbah stepped aside, backing his loyal servant Solomon Berewa. But Berewa lost the election to Ernest Bai Koroma, a businessman who ran the nation like a business, acquiring wealth at a staggering pace. His love for buying things earned him the nickname Adebuyor. The people still await the accounts of his profits.

Like his predecessor, Ernest anointed an heir, Samura Kamara. A seasoned technocrat, but politically inexperienced, Kamara lost to none other than Brigadier Julius Maada Bio, the soldier who once led Sierra Leone back to democracy.

Bio promised a New Direction and hired expert ‘engineers’ to seal the leakages on the Sierra Leonean ship. So far, for every leak they have sealed, two or three new ones have sprung. On the country’s 64th Independence Day, Bio appealed to the people for patience, assuring that things will get better with the investments he has made in education, agriculture, and energy.

Meanwhile, the nation’s haunting past lurks still, as the people continue to yearn for a savior, someone to deliver them a better life.

Note: There’s more to this tale than the teller knows.