By Jarrah Kawusu-Konte

Freetown, August 2025

When Yeama Yambasu’s teenage brother first developed pustules on his face and arms in late 2023, the family thought it was chickenpox. But the blisters rapidly deteriorated, spreading quickly across his body. At the local clinic, nurses looked at him in horror. “Dis na monkeypox,” one whispered.

No isolation, no treatment plan, no referral

Weeks later, Yeama buried her brother in a plastic-wrapped body bag, one of more than 44 recorded fatalities since the monkeypox outbreak began in Sierra Leone in August 2022. Hundreds more have been infected, disfigured, stigmatised, and abandoned to suffer alone.

More than a year into the crisis, the virus still festers. Patients continue to queue at ill-equipped clinics. Families report delays in diagnosis, zero contact tracing, and no compensation or psychosocial support. And the disease, long declared a “Public Health Emergency”, remains unchecked and mismanaged on a scale unmatched elsewhere in the region.

“How can a nation that once triumphed over Ebola now stumble so disastrously against monkeypox?” asked a Public Health expert. “The answer is poor leadership, not viral strength.”

A National Embarrassment – and a Regional Outlier

Monkeypox, now formally known as Mpox, re-emerged in 2022 as part of a global outbreak affecting dozens of countries. While the virus is rarely fatal, it is highly contagious, and outbreaks demand swift response: isolation, testing, contact tracing, community education, and treatment support.

In Nigeria, the national public health agency mobilized an Mpox-specific taskforce and coordinated with WHO to rapidly reduce spread. By late 2023, Nigeria recorded under 5 deaths and had brought case numbers down by over 70% from peak levels. Ghana and Côte d’Ivoire similarly limited Mpox outbreaks to under 200 cumulative cases, according to WHO Africa Region data.

In contrast, Sierra Leone’s outbreak escalated into an uncontrolled public health disaster. According to a joint WHO–CDC situational update (May 2024):

- Sierra Leone accounts for over 25% of Mpox deaths in West Africa

- Confirmed and suspected cases exceed 1,700, more than double the regional average

- Fatality rate of 9.3%, far above the West African mean of 2–3%

- WHO’s emergency advisor in West Africa told The Lancet Global Health in June 2024:

“Sierra Leone’s Mpox crisis is out of step with the rest of the region. The public health infrastructure exists, what’s missing is the political urgency.”

A System That Was Ready — Then Left to Rot

The irony is that Sierra Leone had been one of the most admired countries in the world for post-Ebola epidemic preparedness. The systems created in 2015–2018 included:

- Rapid Response Teams (RRTs) in every district

- A robust Emergency Operations Center (EOC) in Freetown

- Mobile labs and regional diagnostic capacity

- Community surveillance officers and contact tracing architecture

- Pre-existing collaboration with CDC, MSF, and WHO

But most of that infrastructure has been left to decay under the current administration. A 2023 internal review by Public Health England found that over 60% of RRTs were defunct, and key surveillance equipment had not been maintained since 2019.

“The systems were there,” said a former MoHS epidemiologist. “What was missing was will.”

The Human Toll of Government Indifference

For survivors like 29-year-old Alpha Jalloh in Kono, the scars are physical and psychological. “The hospital gave me paracetamol,” he said. “No test, no cream. I lost two toes from the infection.”

Families have been devastated. Businesses shuttered. Children stigmatised and expelled from school.

A grieving mother in Moyamba broke down while speaking to a popular radio in Freetown:

“When my son died, no one came. No test. No burial team. We buried him ourselves.”

Frontline health workers, lacking personal protective equipment (PPE), have refused to treat suspected patients in some districts. Others report going unpaid for months while risking their lives.

“Morale is dangerously low. There’s a sense of betrayal. Ebola taught us what to do. But we’ve learned nothing.”

International Alarm, Domestic Paralysis

It took repeated alerts from MSF, UNICEF, and Africa CDC, before Sierra Leone embarked on vaccination. But what the country needs is to implement a national vaccination strategy for Mpox. While vaccines have been scarce globally, Ghana and Nigeria prioritized high-risk communities and frontline workers. Officials would blame Sierra Leone’s painfully sluggish response on delayed international support. But it’s also largely due to poor planning and preparedness.

Thankfully, the country received a consignment of vaccines just few months ago from WHO. Additional vaccines are expected from DRC. An estimated 133,000 individuals have now been vaccinated, insiders confirm.

“There is no effective or sustained national campaign. Very lax treatment protocol. No urgency,” said a WHO regional advisor. “It is shocking, given Sierra Leone’s experience.”

Meanwhile, public messaging is confusing and sporadic. Billboards about “Stop Monkeypox” have been spotted in urban Freetown, but rural areas, where most outbreaks occur, remain in the dark. It will be impossible to defeat Mpox without the use of an inclusive, people-centred and community focused approach. Examples should have been drawn from both the Ebola and COVID-19 crises.

A New Vision for Public Health Security

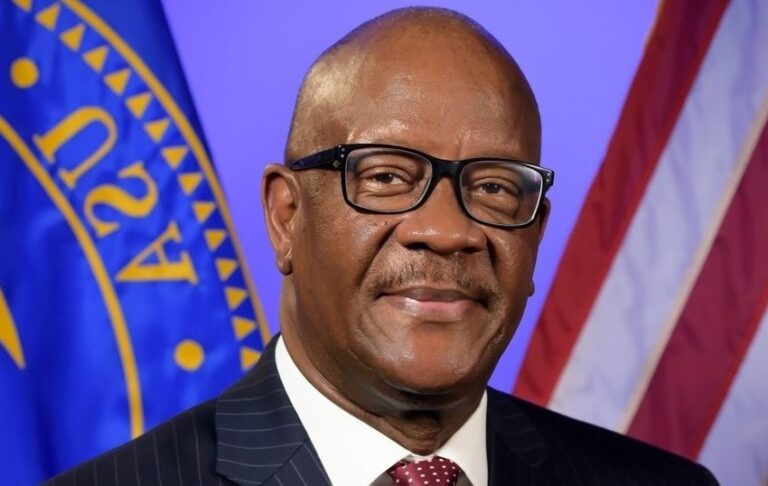

Bangura’s public health strategy, as part of his APC flagbearer platform, includes:

- Reactivating and financing the Emergency Operations Center (EOC) for real-time epidemic tracking

- Permanent epidemic preparedness funding line in the national budget, ring-fenced from political interference

- Rural Epidemic Response Units, locally managed and resourced for rapid containment of future outbreaks

- Community Epidemic Education Corps, to integrate outbreak response into village structures and religious networks

- Securing vaccine agreements through Africa CDC and GAVI in advance of crisis.

“Public health is both a national and human security issue,” Bangura said. “We cannot keep burying citizens because our leaders cannot read the signs.”

Conclusion: A Country That Forgot Its Own Wounds

Sierra Leone, once hailed as a post-Ebola model for epidemic readiness, should have been the best-prepared country in West Africa to face Mpox. Instead, it has become the worst-hit with over 100 new cases in the last three weeks, bringing the total to 5,106 with 117 active cases and 49 deaths (8 August, 2025).

The suffering of families like Yeama Yambasu’s is not the result of some unpredictable plague. It is the result of systemic neglect, political silence, and chronically inefficient public health services.

As Dr. Bangura often reminds supporters:

“Monkeypox will not be able to defeat us, if we are better prepared. What we need is bold, direct and effective leadership in tackling the disease”