January 26, 2026

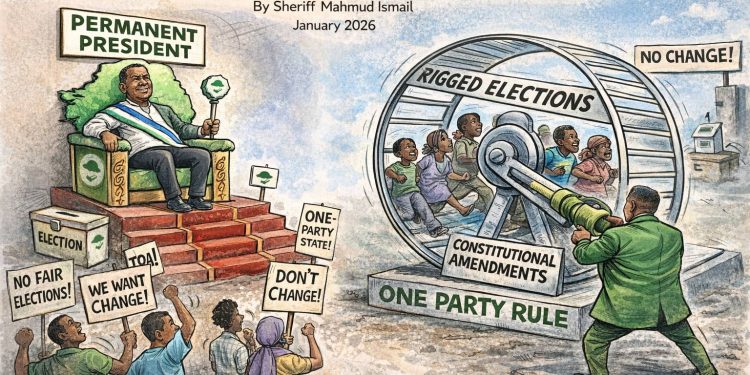

If the first task of a constitution is to restrain power, the second is to ensure that political competition remains real. Across the world, history is littered with instances of dictatorship creeping in without seizing power, without rolling any tanks, without cancelling any elections—and yet the outcome is quietly narrowed.

As we have seen in many African countries, election seasons are increasingly feelingfamiliar. Campaign billboards and party songs flooding the streets. Candidates crisscross the country. Ballot papers are printed. International observers arrive and voters queue under the sun—hopefully, patiently, dutifully.

Then, when the result arrives, the same party wins, the same man remains, sometimes, the same family continues.

And the most unsettling truth is this: nobody is surprised. Uganda. Cameroon. Congo-Brazzaville. Equatorial Guinea. Togo.

These are not countries without elections. They are countries without alternation. Power does not change hands, not because people do not vote, but because the political system has been engineered to ensure that voting changes nothing. Sierra Leone stands at such a moment with deep concerns about the proposed 2025 constitutional amendments. This is particularly when viewed through the lens of electoral history, census politics, boundary reconfiguration, and the lived experience of opposition parties, most notably the All Peoples Congress (APC).

The African Trap: When Democracy Becomes a Ritual

Across Africa, the most enduring systems of political dominance have learned that sophisticated undemocratic lesson: you don’t have to cancel elections to control outcomes. You only need to redesign the conditions under which elections take place. Political scientists Steven Levitsky and Lucan Way describe this model as “competitive authoritarianism” – systems where opposition parties are legally allowed to exist and elections are regularly held, yet the playing field is tilted so decisively that incumbents almost never lose.

This is because Africa’s modern political pattern shows that democracies no longer die bytanks. More often, they die by devious constitutional reforms.

In all the five countries highlighted above, the tragedy is not that elections disappeared. The tragedy is that elections became ceremonial legitimacy—democratic theatre that masks political permanence. Over time, opposition parties find themselves permanently disadvantaged—not banned, but boxed in. A democracy in which one party repeatedly wins because the rules increasingly favour it. The trouble is: when elections no longer offer meaningful choice; when opposition becomes symbolic, voters will disengage, and politics migrates from ballots to grievances. We were there before with atrocious consequences, but it seems the Sierra Leone politicians have not learnt anything from the country’s brutal past. With those regrettable proposed amendments, Sierra Leone is once again edging dangerously close to that reality.

A Call for APC Unity

This is the moment that demands discipline. For the APC national leadership, its parliamentary caucus, and local council, the message is stark: fragmentation now is self-defeat later. Internal disagreements, however justified, pale beside the risk of structural marginalisation. Recent parliamentary votes, including the failure to hold a united APC position during the removal of Auditor General Lara Taylor-Pearce, have already weakened public confidence. This Bill is far more consequential. APC MPs, including the renegade Mohamed Bangura and Alfred Thompson, must recognise that party unity at this juncture is not loyalty to individuals. It is loyalty to political survival and democratic balance. Failure to act collectively will not punish party leadership. It will entrench a system in which opposition becomes ornamental.

Beyond the APC: A Democratic Imperative That Must Transcend Party Lines

This is not an APC problem alone. It is a national one. I commend Mohamed Gibril Sesay Marcella Macauley , head of the National Elections Watch, Basita Michael

Idriss Mamoud Tarawallie, and ILAJ for adding their perspectives on this all – important political development. Other Progressive civil society, governance experts, academics, the legal profession, independent media, and citizens, including SLPP supporters and Members of Parliament who care about democracy and fair competitive elections, must speak out, recognizing that political leaders come and go but constitutions remain. Fragmentation and/or silence will be interpreted as acquiescence. That would only mean that the amendments will pass and if they do, their consequences will be felt long after the headlines fade.

The response must be strategic, effective, coordinated and a unified resistance grounded in constitutional principle:

Clear public explanation of how technical reforms affect everyday voting power.

Sustained media engagement, beyond party platforms, to appropriately frame the issue as democratic, not partisan.

Concrete alternatives, including retention of FPTP with targeted inclusion reforms such as gender quotas and campaign finance transparency.

Direct engagement with development partners, regional, continental and international organisations, as well as diplomatic missions in Freetown, principled pressure grounded in democratic norms.

This campaign must underscore that it is not about blocking reform. It is about preventing reform from becoming entrenchment. Dominance achieved through rules is harder to reverse than dominance achieved through force.

In my next article, I will explain how the proposed amendments hold the possibility of becoming a “Machinery of Permanence” that eliminates political opposition.